The First Foot Guards

We are a Revolutionary War

reenactment group based in Boston MA,

accurately portraying the royal household regiment that is now known as

The Grenadier Guards

In the eighteenth century, Britain's most important industry was the production of textiles, and among those exports, wool was preeminent. It clothed the Redcoats, and most of the soldiers they fought, too.

A brief history of the woolen industry

in England

and a few of the family names that come from this trade.

Wool

After the Norman Conquest, export trade was inextricably linked with wool,

and European textile markets were heavily dependent upon the English raw wool.

Sheep farmers and cottagers were scattered all across the realm, each doing

their small part in the greater whole. The English wool export trade, its

main economy, was a cottage industry. Wool trading quickly became a highly

profitable means of making money.

The importance of wool is reflected in the presence of the Woolsack upon which the Lord Chancellor in Parliament sits. It was introduced by King Edward III (1327-77) and was stuffed with English wool as a reminder of England's traditional source of wealth - the wool trade - and as a sign of prosperity. You could well compare it to the golden cod hanging in the Massachusetts State House. Both are no longer symbols of the main industry, yet they remain as symbols of prosperity.

In 1056 the Count of Cleves had jurisdiction from the Holy Roman Emperor over the burghers of Nijmegen on condition that he paid the nominal annual rent of three pieces of scarlet cloth of English wool. At this period the wool would have been imported, prepared, woven and dyed by the burghers, the fine red-dyed wools of England were centuries away.

The wool men of East Anglia, Devon and

the Cotswolds, and the Midlands rapidly became prosperous. These medieval

merchants bought fleeces from the small farmers or from middlemen employed

by them. Their wool collectors carried it on a string of laden packhorses,

going round of the farms, finally taking their loads to wool markets. Markets

were held on specific dates at strategic towns where the local men would meet

with merchant traders from across Europe, especially from France, Flanders

or Italy.

The cloth towns of the Low Countries (Bruges, Lille and Arras) were closely

linked with England by the trade in raw wool. England produced excellent fine

wool, but lacked the skilled craftsmen to make the finest quality cloth.

The prosperity of the wool merchants is reflected in the fine houses they

built for themselves, and the churches they endowed. In the Low Countries,

the large Cloth Halls are reminders of their wealth and power. There are still

many moorland pubs in England called 'The Pack Horse' to remind us of the

old trails.

In 1340, 30,000 sacks of wool were granted to King Edward III to support the French war. This was worth a considerable amount of money.

Woolen Cloth

There are records of payment for cloth made in the early 1200s, but the export of finished fabric was insignificant until after 1300. For example, the market in Exeter sold over £10,000 of yarn and wool in the year of 1536. At the end of 1540 this had fallen to £5000.The trade in wool cloth now exceeded it, with £100,000 worth of serge each week leaving the Staple of Exeter.

Successive monarchs taxed the wool trade,

especially when they had special need for added revenue, such as in times

of war. A system gradually became established under which, by royal ordinance

wool could only exported through a limited number of specified towns known

as the staple towns. In the end there was only one staple town in continental

Europe: Calais. Thus the merchants of the staple in Calais had a monopoly

over the sale of all English wool to Europe. This had an unintended consequence

of driving up wool prices, which in turn drove up the prices of the cloth

manufactured in Europe.

Before this time, England was a net importer of woolen fabric, but now that

European wool was more expensive, it now became worthwhile to manufacture

cloth at home. The staple monopoly in Calais destroyed itself prior to the

fall of the town to the French in 1558, and England became the greatest cloth

producing country in the world.

Over the centuries, many other laws were passed to regulate this all-important trade. Presaging the woes of the industrial revolution, a complaint that shoddy goods were being made by mechanization was laid in the reign of King Edward IV: " That hats caps and bonnets had hitherto been made and wrought and fulled in the wonted manner, with hands and feet (mayns et pees). The mills bring inferior articles to the market." Translated from the Anglo-French in which law pleas were written.

In order to promote the wool trade, King Charles II passed an act of parliament in which it was an offence for someone to be buried without being wrapped in a woolen cloth, and the fine imposed was £5. Thus "wearing a linsey-woolsey gown" became common parlance for death. The act was in force during our First Foot Guards period (1776-1783), and was not repealed until 1814.

Spinning had been done originally with

a spindle and distaff, and was made simpler by the introduction of the spinning-wheel

in Nuremberg in the 1530s. It consisted of a revolving wheel operated by treadle

that drove a spindle. The process was unchanged until James Hargreaves invented

the Spinning Jenny in 1764. This was a fatal blow to cottage industry.

At first worsted spinning frames were introduced into the cottages and for

a while the operators had a monopoly. Carding and spinning was done mechanically

in the factory but the weaving was still being done by hand. During the 19th

century the hand weaving trade briefly boomed again, bringing weavers into

the towns to sell their serge. Local populations expanded dramatically but

it did not last and very soon mills closed as the boom in trade ceased. Changes

in policy in the 19th century opened up the wool trade to international pressures.

Huge mechanized factories were erected in the North of England (especially

around Leeds - the fleece features prominently in the Leeds civic coat of

arms).

Power loom weaving was introduced in the 1820s. Entrepreneurs in Yorkshire

were more likely to employ steam power than in other areas. The woolen industry

declined rapidly in Devon, Somerset, Wiltshire, and Gloucestershire and East

Anglia. By the 1830s the long association with the wool cloth trade finally

ceased in the old towns. The East India Company could no longer find buyers

for serge and dumped it on their Chinese market, making a loss in the process.

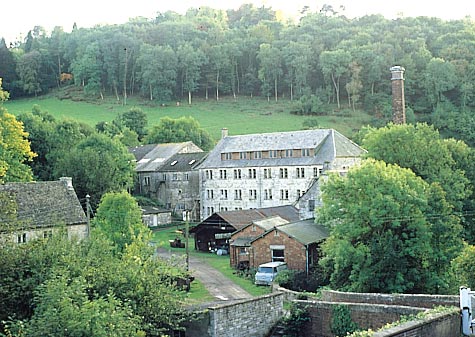

A Stroud valley woolen mill.

Leeds in Yorkshire had become the market center where the cloth was exchanged

and finished. The output of broadcloth in the area rose from 30,000 pieces

in the late 1720s to 60,000 pieces in the 1740s. Leeds now covered 60 acres

and by 1770 the town had a population of 16,000. Thirty years later, this

figure had doubled.

Family wool trade names

Unlike any other trade (except for that of Smith), the importance in England

of the wool trade has given rise to hundreds of family names.

Shepherd - tended the sheep.

Pack/Packer/Packman and Lane/Laney/Lanier - transported the fleeces.

Stapler/Staples (bought the raw wool)

Card/Carder, Tozer/Towzer, Kemp/Kemper/Kempster (= comb) combed the wool

Dyer, Littester/Lister dyed the wool.

Webb/Webber/Webster (German: Weber) wove the fabric.

Fuller, Tuck/Tucker/Tuckerman, fulled the fabric to create a nap.

Shears, Sharman/Shearman used shears to remove the nap from woolen cloth to

produce finer qualities of fabric.

Clothier and Draper - prepared the woolen cloth and sold it to the tailors.

Taylor and Cutter - made the wool into garments.

There are also many place names based on wool that have become family names: Woolley, Wolsey, Shipley/Shepley, Sheppey, Shepperton, Shefford/Shifford, Shipton/Shepton [sheep-lea, sheep-town].. just to name a few.

Where did the red dye come from for those woolen coats? Onsite link.

See the beautiful old stone Cotswold woolen

mills

Offsite link

NEXT

ARTICLE

Go to

"This Date in History"

Click