The First Foot Guards

We are a Revolutionary War

reenactment group based in Boston MA,

accurately portraying the royal household regiment that is now known as

The Grenadier Guards

There's more to macaroni than cheese.

By Graeme Marsden

We all know of the 'macaroni and cheese' made famous by JL Kraft, and we know of the 'macaroni' reference in "Yankee Doodle", but there's more fascinating information about this fashion fad that would still be fresh in everyone's memory in 1776. James Boswell wrote about 'the Macaronis' in his "Life of Samuel Johnson" in 1773.

A little fashion background.

After the restoration of King Charles II in 1660, fashions changed, becoming more flamboyant. (Anything was more flamboyant than conditions under Cromwell!) London reverted to becoming a leader in fashion trends, along with Paris, and when King Charles adopted the French wig, so did all of his courtiers. Samuel Pepys comments about his first purchase of 'a periwigg' in his famous "Diary", noting that he at first had trepidation, but when he went to church wearing it, he was mortified that nobody noticed his new expensive purchase.

Wigs had actually been introduced to the French court in the previous century. In 1521 the young King Francis I had been out roistering in the snow, and had been burned by a flambeau. To cover his injuries, he began to wear a wig. His courtiers followed suit. Such slavish copying of the court was not unusual: when a Spanish king lisped, the courtiers copied it, giving us the aristocratic pronunciation that is common in Spain today.

In the next century the 'Sun King' Louis XIV said he would not wear a wig, but when he began to go prematurely bald in his 20s, he adopted this headpiece, and its success was assured. Interestingly enough, when Louis' moustache began to show gray, he cut it off. So too did all the fashionable gentlemen at the French court.

Back to London. Early pictures of Charles II show him in doublet and breeches, usually with 'petticoat breeches' (with lots of ribbons at the lower hems.) Later in his reign, the coat slowly became fashionable, and with it the standard three-piece ensemble we know today (coat, vest/waistcoat, and breeches/trousers). Early examples of the coat date from 1663. With the coat and the wig, the broad lacy 'falling collar' became inconvenient, and it vanished. The high hat (Pilgrim hat) of the Commonwealth gradually began to lose its height as the century progressed, and towards 1700 began to be cocked (or turned up at the edge). At first, only one side was turned up at a jaunty angle (left, right, front or back), but by the early 1700s the hat was almost universally 'three-cornered'. Some country folk and scholars wore them uncocked (Laver, page 137).

Coats at first had enormous cuffs, and you can actually date the coat from their length (they got shorter as the century wore on. The same is true of the waistcoat. It was long in the French & Indian War period, decreasing to the waistcoat of two points of the Revolutionary war era, to the straight cut garment of 1800.

Servants and lawyers always wore what the fashionable people wore in the previous generation, and wigs persisted well into the 1800s. Barristers and judges still wear them in England. Old men in every age were mostly reactionary, continuing to wear just what they wore in their youth. For example, Paul Revere, who died in 1818, never adopted trousers, although he looked very old-fashioned.

By 1680 the wig had gotten enormous, full-bottomed, and high on top. As wigs became more conservative after 1710, the time was ripe for a reaction, which this time came from the young men.

The Macaronis

Fashion changes are a history of gradual change (the length of the cuff, mentioned earlier) or one of reaction: short hair of the Puritans gave way to long hair of the Restoration. The Macaronis were a youthful reaction.

By the 1750s it had become de rigeur for rich young men to tour Europe (especially Italy) in a 'Grand Tour'. Here they absorbed different cultures, ate different foods, studied art, drank heavily and chased young women. It was in many ways a rite of passage.

When these men returned to London, they brought the pasta dish 'macaroni' with them. To set themselves apart from the establishment, they began to wear outrageous costumes.

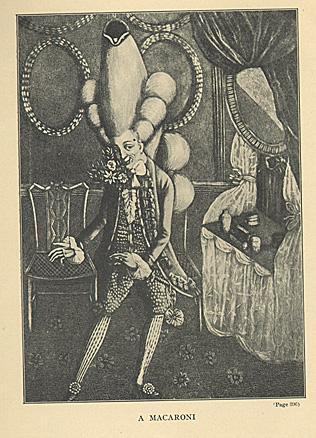

The wig was worn with large side curls, and very high in front (up to 9" high), with almost a vestigial three-cornered hat perched on top. (This style actually was picked up by the ladies, and their hair reached enormous heights in the French court in the early 1780s when Ben Franklin was there). The Macaronis carried or wore nosegays of flowers (attached to the right lapel), wore tightly-fitting coats and short waistcoats with enormous buttons, and exquisitely thin shoes (we might today call them "Italian"), with huge buckles of gold or pinchbeck. They also affected a mincing gait, which actually might have been necessary with their delicate shoes, tight garments and top-heavy wigs. The presence of these 'exquisite young fops' did not please the older gentlemenů to say the least. You can well imagine the comments that were called out in the streets.

Because they were associated with 'foreign food', these dandies became known as 'The Macaronis'. The term may have been applied to them, or they may have adopted it themselves. At any rate, the first mention of them as such comes from 1764.

The bastion of the traditional English county look at this time was The Beefsteak Club. This was an establishment where the patrons (though wealthy) considered themselves as a down-to-earth, no-frills kind of people, with conservative clothes such as the rugged leather shoes and boots they wore. It was natural that there should be a 'Macaroni Club'. They were mercilessly lampooned both by satirists and caricaturists.

"The Maccaroni Club, which is composed of all the travelled young men who wear long curls and spying glasses." Horace Walpole, 1764.

The macaronis and those who tried to copy them adopted what was most extreme in male fashion. Their outraged elders began calling anything that was new or outlandish 'macaroni'. For years, the word was a synonym for an overdressed young man on both sides of the Atlantic, so that Yankee Doodle, when he came riding into town on a pony, 'stuck a feather in his hat and called it macaroni'. The song originally parodied the rusticity of the Americans. Naturally they could not aspire to high fashion, and their attempts at such were thought of as ludicrous.

In this day and age we might well call such a failed attempt as "cheesy".